If you’ve been online at all for the past two weeks, or watched the news, or talked to someone, or are part of civilization right now and not just wandering off into the Wild like Reese Witherspoon, you are aware of the events that are taking place surrounding the Grand Jury decisions in the cases of Eric Garner, a black man choked to death on camera by New York Police officers, and Michael Brown, a young black man gunned down by an Officer in Ferguson. Neither of these Officers were indicted, and the results have sparked protests and visible unrest throughout the nation, including social media hashtags like #blacklivesmatter, #handsupdontshoot, and #icantbreathe.

Ferguson was the catalyst for the social media discussion and viral protest, and then the Eric Garner decision in New York only further escalated the anger that many Americans felt at seeing a gross and corrupt system that is allowing Police Officers to go free of punishment for taking black lives. Now, if you type those hashtags or names or keywords into any search engine, you are sure to see pictures of people holding signs, doing “die-ins” (laying on the ground in large groups in public spaces) or school walkouts, all over the country. However, I believe in the heart of this social unrest and protest, there is a serious disconnect happening in which #blacklivesmatter is meaning two separate things for two different populations, and it is going ignored under the illusion of true solidarity.

The “#blacklivesmatter” and “#icantbreathe” hashtags can be understood as cultural texts within the social media landscape, meaning that they are works open to interpretation and different use based off of a constructed meaning by each individual who is using them. They were started with a very deliberate intention and meaning, but once they hit the social media sphere and become active texts, that original meaning no longer matters as much as the new meaning that will be ascribed, or coded, onto them by twitter, Facebook, and Instagram users. The disconnect that I think exists is that generally, “Black Twitter” and people of color are seeing an opportunity to express sentiments that they have felt for years, and are witnessing a peak in an ongoing battle. On the other hand, there are well intentioned white people who are having a reactionary response to these recent events, and instead of understanding that there is a flawed and racist institutional hierarchy, and that ALL #blacklivesmatter within the oppressive hierarchy, they are reacting only to THESE specific deaths, and THESE specific injustices. When white people are saying #icantbreathe they’re saying how awful Eric Garner’s death was and seeking justice for the cop that killed him. When Black people use it they’re saying #icantbreathe day to day in a system I’ve been suffocating under my whole life.

Most white people right now are reacting like Rowdy Roddy Piper in THEY LIVE when he puts on the glasses for the first time and sees how fucked up everything is. People of color are like the underground resistance in the movie who have known that this shit has been going on since long before the glasses to make it visible even existed. While the coalition and welcoming of any people willing to fight for a cause is welcome, I believe that these separate and mostly unspoken perspectives are allowing an opportunity for social change at an institutional level to become watered down to gathering masses of angry individuals being angry together, unaware of how to take the next step toward change beyond hashtags and awareness. I don’t want to be misunderstood as saying that awareness is a bad thing, but it is the first step toward making real change, and when awareness is just being raised among other folks who are already aware, there is less of a movement toward change and more of a stagnant mass unrest that eventually disperses.

When using the label of “Protest,” as opposed to a large gathering of people making noise, I think there needs to be context of what successful protests have looked like in the past, and to understand that on a fundamental level, most, but not all, of what is happening right now surrounding the Grand Jury decisions, is not a successful Protest. Malcom Gladwell outlined in a 2010 New Yorker article how Civil Rights protests (which are pretty much the established aesthetic of what a protest looks like for millennials) were organized systems, with dedication, strong-ties and relationships between human beings, and disciplined authority structures designed to have leadership to make hard decisions and direct the networks of protestors. This system of organized protest, much more than a Facebook invite to meet up in the campus student center with a sign, were effective at seeking ways in which people within the power structure of flawed institutions could be directly taken to task and held accountable to use their power for change. There was dedication and there were organized and directed political objectives, which goes beyond the images our generation has been fed of the million man march and even three days of peace and music being all that was necessary to make change.

Twitter does not hold anyone accountable. Facebook does not take authority figures to task. These protests are becoming, quite literally when you look and the cardboard signs and t-shirts, physical manifestations of hashtag “revolution.” On my campus, I have seen people do a “die-in” at the student center, and know that 4.5 minutes of silence were organized on the plaza through a Facebook organized meet-up, and saw statuses glorifying the “protests” for being able to just be there with everybody and hug strangers and share the moment. Well after the self-congratulatory stranger hugging is over and the groups disperse, these weak dies are broken and not one authority figure or hierarchical system has been challenged or taken to task. The protests were not even anywhere close to the Administration building or campus police force, directly addressing anyone who, even on the smallest scale, could make any kind of real systemic change. It’s nice to spread tweets and pictures letting people know you’re mad, but being mad doesn’t disrupt anything, it just creates noise.

If the system of injustice is a man (more like “The Man”) walking down the street and you see him, standing behind him and shouting will just allow him to walk away. Following behind him and shouting will keep creating noise, but he can just as easily keep walking. But by standing directly in front of The Man and shouting in his face, refusing to get out of his way until he makes a substantial change to the situation that meets your demands, you have just created change. You forced someone in a position of power to make a change. It could create conflict. He could punch you square in the fucking face. But I think maybe that’s what protest is. True protest is the willingness to get in the way and challenge authority, to risk getting punched square in the face, and to get back up as many times as you can and repeat, until the system of oppression that’s punching you has a broken fucking hand.

You can tweet or hold a sign, reminding everyone, and maybe even yourself having a crisis of privilege realization, that #blacklivesmatter, but what can you actually organize and accomplish that forces a historically racist institutional hierarchy to change on a fundamental level so that people know for a fact when they leave their home that all #blacklivesmatter?

The last thing I want to say is that my grandparents and most of their generation were aware of the way Black people were treated daily. They participated in it. Not everybody, but definitely a lot of old white people were fully aware, and didn’t give a shit, and still don’t. If there were hashtags notifying them that the Little Rock 9 were being integrated, they still would’ve opposed it. But the protests that constituted Civil Rights Movement, because of the organization and leaders within all oppressed communities including Chicano, Asian, Black, Women, and all of their intersections, directly attacked institutions and racial hierarchies. They took over buildings that represented oppression, they disrupted the system by getting in front of its leaders and forcing change, and they made or changed policy that was the direct source of institutional oppression. While not everything worked, or was perfect, or successful, the change that was made has a lasting effect and is engrained now as slight improvements within oppressive institutions that still require overhaul. The past protests forced new systems and laws into place that racist and ignorant people just had to learn how to tolerate, and still have to until they die off and leave the world in younger generations’ hands.

There still is a long way to go, but if the best we can do is tweet and post our frustration to be read only by others who feel it, and organize cathartic gatherings that refuse to directly challenge oppressors in exchange for the “feeling” of doing something powerful, then we’re failing to take the necessary steps to evolve the successful protests of the past, and all of the injustice that everyone is so angry about remains in place. If all we can do is tweet and post at the system, then all it’s going to do is block us and hide us from its newsfeed.

So backtracking a little bit, the timely release of the independent film “Dear White People” directly dealt with the issue of appropriation. SPOILER ALERT. The climax of the film was a frat party, based off of numerous real parties that are displayed in the end credits, where white students get together in full black face, costumed as various “black” caricatures such as rappers and gangsters, in order to push back against black students who are protesting campus racism. In the climactic scene, much of the films “say more show less” style flips around, and the implications of what is happening are left to sit with the audience for contemplation. The only moment of the scene where a character directly articulates any kind of way to feel toward the audience is when CoCo says that for a night, the white people got what they wanted, which was to be black. Ultimately, the character is suggesting that appropriation happens because white people really just want to be black.

So backtracking a little bit, the timely release of the independent film “Dear White People” directly dealt with the issue of appropriation. SPOILER ALERT. The climax of the film was a frat party, based off of numerous real parties that are displayed in the end credits, where white students get together in full black face, costumed as various “black” caricatures such as rappers and gangsters, in order to push back against black students who are protesting campus racism. In the climactic scene, much of the films “say more show less” style flips around, and the implications of what is happening are left to sit with the audience for contemplation. The only moment of the scene where a character directly articulates any kind of way to feel toward the audience is when CoCo says that for a night, the white people got what they wanted, which was to be black. Ultimately, the character is suggesting that appropriation happens because white people really just want to be black.

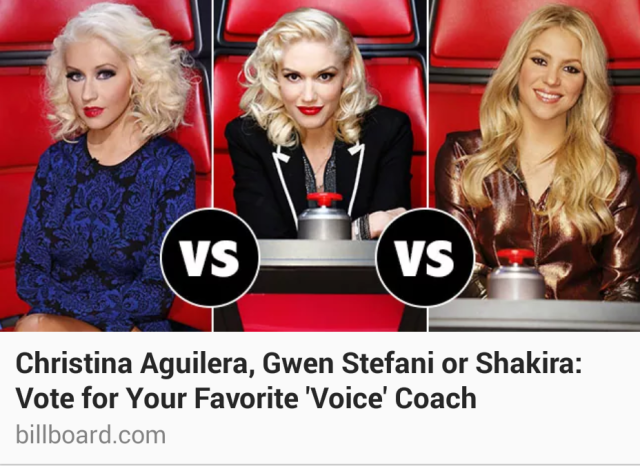

The ideas of assimilation and beauty stem from the black and white body binary, where in order to be successful in the mainstream, or at the very least have an opportunity to try, women of color become as close as they can physically to the white ideal which has been force fed down our throats as what beauty looks like, attempting to get rid of the enlarged features of their bodies, that are used to identify black female bodies as an Other.

The ideas of assimilation and beauty stem from the black and white body binary, where in order to be successful in the mainstream, or at the very least have an opportunity to try, women of color become as close as they can physically to the white ideal which has been force fed down our throats as what beauty looks like, attempting to get rid of the enlarged features of their bodies, that are used to identify black female bodies as an Other.

The Dragon Woman is mysterious, she’s deceptive, she’s in a position of power which she executes in a brutal fashion, and she’s shady as hell. Mooney fits all of these descriptions, and for Christ’s sake, her lair is in Gotham’s China Town. So although GOTHAM breaks form so far by representing crimes in a non-typical manner, it is partially due to the fact that there are just not many black actors cast, and the biggest one that is cast is being characterized in a fashion usually reserved for Asian women. This could be positive in the way that applying a stereotype to someone it doesn’t apply to normally diversifies representation by showing no one group or people fit into that type, which in this instance is the Dragon Woman Type. It could also still be just as negative by portraying a woman of color in power as villainous and shifty, as well as continuing to reinforce the elements of the stereotype for further production.

The Dragon Woman is mysterious, she’s deceptive, she’s in a position of power which she executes in a brutal fashion, and she’s shady as hell. Mooney fits all of these descriptions, and for Christ’s sake, her lair is in Gotham’s China Town. So although GOTHAM breaks form so far by representing crimes in a non-typical manner, it is partially due to the fact that there are just not many black actors cast, and the biggest one that is cast is being characterized in a fashion usually reserved for Asian women. This could be positive in the way that applying a stereotype to someone it doesn’t apply to normally diversifies representation by showing no one group or people fit into that type, which in this instance is the Dragon Woman Type. It could also still be just as negative by portraying a woman of color in power as villainous and shifty, as well as continuing to reinforce the elements of the stereotype for further production.