Note: This you may want to check out last week’s post on appropriation of “booty,” which this post will somewhat be a continuation of.

Note: This you may want to check out last week’s post on appropriation of “booty,” which this post will somewhat be a continuation of.

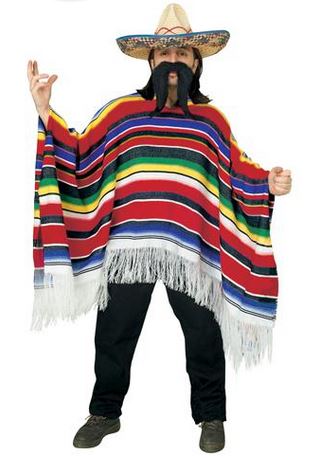

On the lead in to Halloween, college campus student organizations and social media outlets of more liberal minded folk attempt to raise as much awareness as they can about the racism behind dressing up as another culture as a Halloween costume. This usually includes things like white folks wearing black face, or sombreros, or knockoff Native American head dresses and garments, all as costumes, with no respect to the fact that they are portrayals of non-white races, ethnicities, cultures and experiences for the sake of entertainment and exploitation by (usually) white people outside of those groups. Dressing up like this, on Halloween or any other day, means that those people dressing up are committing a racist act, and therefore an act of violence against another group.

So first of all, I want to take a moment personally to say fuck you to those people. But second of all, I want to make it clear, now that Halloween is over, that my “fuck you,” along with the social justice work done by people trying to raise awareness for this issue constantly, is falling on deaf ears.

On Friday night as I drove down to Old Town Ft. Collins’, where the costumed student population congregated for Halloween festivities, I saw three individuals who were proudly dressed as two Ku Klux Klan members, in full hoods and robe, each holding the ends of a rope that was wrapped around the neck of the third individual, an African American male, with a smile on his face. And don’t misunderstand this as a white person in black face, to be absolutely clear it was two white men and one black man, participating hand in hand, or more accurately neck in rope.

Read that again and let it sink the fuck in, please. ‘Cause I still haven’t completely come to terms with it, myself.

These folks, mingling joyfully with the crowd, were the bright racist cherry on top of a day filled with loads of kids on and around campus wearing their sombrero/poncho combos (#1 Most Common Offender I saw), and cheap colorful “Native” feathers (#2). I would hope that in a perfect world, someone said something to the KKK triplet, and that the reason they were walking away wasn’t because of crowd dispersal but was because they were publicly shamed. I’d like to say that these costumed white people were just ignorant, waiting to be informed about the problems with their poor decision, and recognizing why it was wrong. However, I don’t think we live in a perfect world. I don’t believe that it’s right to slight someone for ignorance, but it is acceptable slight them for refusing to amend it. These people all most likely saw or heard warnings against cultural appropriation on Halloween, and although ignorance and lack of understanding as to why it’s wrong may still may be a part of it, they didn’t think twice about the concerns of marginalized groups, and that’s just pure, mean, disrespectful hate.

Author Bell Hooks describes the commodification of Otherness, which is what is happening here with the appropriation of cultures and ethnicities as costumes, as being a spice or “seasoning that can liven up the dull dish that is mainstream white culture” (from Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance). Ethnicities that have become “Othered” to reinforce white supremacy become commodities to be consumed and exploited by dominant white culture, which is the mechanism through which appropriation expresses itself. Appropriation is a violent display of power and consumption, fueled by ignorance and lack of understanding of cultural contexts and historical injustices, with complete disregard by the participating individuals to correct their mistakes, or educate their ignorance.

So backtracking a little bit, the timely release of the independent film “Dear White People” directly dealt with the issue of appropriation. SPOILER ALERT. The climax of the film was a frat party, based off of numerous real parties that are displayed in the end credits, where white students get together in full black face, costumed as various “black” caricatures such as rappers and gangsters, in order to push back against black students who are protesting campus racism. In the climactic scene, much of the films “say more show less” style flips around, and the implications of what is happening are left to sit with the audience for contemplation. The only moment of the scene where a character directly articulates any kind of way to feel toward the audience is when CoCo says that for a night, the white people got what they wanted, which was to be black. Ultimately, the character is suggesting that appropriation happens because white people really just want to be black.

So backtracking a little bit, the timely release of the independent film “Dear White People” directly dealt with the issue of appropriation. SPOILER ALERT. The climax of the film was a frat party, based off of numerous real parties that are displayed in the end credits, where white students get together in full black face, costumed as various “black” caricatures such as rappers and gangsters, in order to push back against black students who are protesting campus racism. In the climactic scene, much of the films “say more show less” style flips around, and the implications of what is happening are left to sit with the audience for contemplation. The only moment of the scene where a character directly articulates any kind of way to feel toward the audience is when CoCo says that for a night, the white people got what they wanted, which was to be black. Ultimately, the character is suggesting that appropriation happens because white people really just want to be black.

Now this is a complex scene, with much more being communicated visually than just this sentiment, however because it’s the only verbally articulated understanding of the situation, it’s worth addressing. I would argue that it is overly simplified, and problematic to communicate to a white audience who has no problem with cultural appropriation.

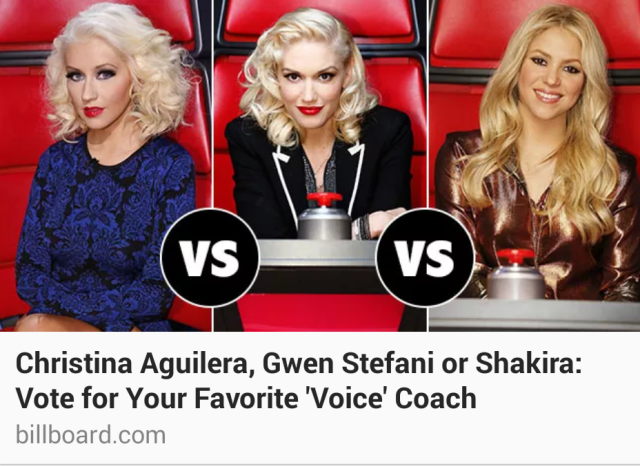

While it seems that in pop culture, there is a need to be more “black” coming from artists like Miley Cyrus, Taylor Swift and Iggy Azalea, who have appropriated aspects of hip-hop that are tied historically to black female artists, and who have claimed they were looking for a “black sound” while relegating black people to the background of their videos, none of this is as simple as just wanting to “be black.” There is a massive commodification of styles, and more importantly sexual features, that have been condemned on the black bodies that they have been linked to, but are now being sold as products on the white bodies that are trying to claim ownership of them. The root of these changes is not artists wanting to be black, its artists and their companies wanting to make money by exploiting the Other.

The appropriation by white female artists trying to sell their bodies by promoting enhanced sexuality that has been condemned on black female bodies has sparked a pushback by Black female artists like Nicki Minaj and Beyoncé to attempt to take control and ownership of their bodies, and their previously condemned sexuality which they recognize is being commodified for whites. While it is still debatable about what they are accomplishing by claiming feminism and sexual liberation, it is clear that they are attempting to regain control of their own bodies, suggesting that if commodification is going to happen, then they will be the ones who will have control and power over their product.

But even this resistance is now appropriated, as evident by the video for Mastadon’s single “The Motherload,” in which Minaj-esque dancers saturate the screen, with full slow motion twerking and booty shaking, culminating in a dance battle with their dancing bodies on full display. This video is evident of the same kind of ignorance based power play that comes with dressing up to mock another Race or culture. Mastadon is appropriating the visuals, no matter how problematic they may be, that Nicki Minaj attempted to use to regain control of the black female body. “Motherload” delegitimizes and mocks her attempts at agency, while profiting off of the trendiness of her image and video. The drummer for Mastadon told Pitchfork that he hadn’t seen the Minaj “Anaconda” video, which if honest, still leaves the director and all other band members to know exactly what they are capitalizing on.

Mastadon received pushback, and controversy was created, but they took that opportunity to further capitalize, launching a contest that encouraged their largely white male audience to display their best “twerking,” leading to pictures openly mocking the Minaj visuals once again, as well as creating “asstadon” booty short, and a t-shirt of an enlarged-booty witch, with a pumpkin taking the place of her butt, just in time for Halloween.

This appropriation in pop culture is coming from the same place as Black Face. Whether it’s Mastodon appropriating black bodies to recall images of “Anaconda,” or white female pop-stars singing about their booty and desire for a “black sound,” it’s the same supremacist philosophies behind different forms of expression, and it continues to happen.

When it comes to pop culture, you have the option to vote with your dollar. You have the option to not participate in the exploitation race and culture by not buying what their selling, and by not contributing to corporations profits so that they produce more of the same at the expense of Others.

However, when it comes to the micro-scale, like seeing friends and colleagues dressed as “Mexicans” and “Indians” as Halloween costumes, the struggle to do the right thing increases as the desire to avoid personal confrontation weighs down. But we need to be able to have these discussions and tell these people what they’re doing is wrong. And if these messages continue to fall on deaf ears, then maybe we need to step up our game. Maybe we meet their pushback with more pushback, by any means necessary. Or maybe we just keep having the conversations with hopes that it all works out in the end… That doesn’t seem likely, but I’m not really sure there’s a definite answer.

I know that one thing you can do is go see movies like “Dear White People,” and let studios and people in power know that we want more of that kind of media made available, because while it’s not perfect, and no movie ever will be, we need to support more media that continue to try to have discussions about race, gender, sexuality, and class in ways that audiences can comprehend, and that keep a healthy and constructive conversation going.

The ideas of assimilation and beauty stem from the black and white body binary, where in order to be successful in the mainstream, or at the very least have an opportunity to try, women of color become as close as they can physically to the white ideal which has been force fed down our throats as what beauty looks like, attempting to get rid of the enlarged features of their bodies, that are used to identify black female bodies as an Other.

The ideas of assimilation and beauty stem from the black and white body binary, where in order to be successful in the mainstream, or at the very least have an opportunity to try, women of color become as close as they can physically to the white ideal which has been force fed down our throats as what beauty looks like, attempting to get rid of the enlarged features of their bodies, that are used to identify black female bodies as an Other.

Black-Ish follows a trend started by the Cosby show of representing African Americans, and more specifically African American families, as intelligent, successful, and loving, as opposed to poor, or violent, or buffoons, in order to counter these images that saturated the media. When the Cosby show aired, the black families seen on TV were either in the Ghetto and needed white aid to get out, or had made it out of poverty but the fact they now co-mingled with rich or middle class white people was a punchline. Many images of African Americans still portrayed them as comedic buffoons on TV, re-presenting old images of minstrels or “Coons.” Cosby understood how harmful these images were and saw a necessity to provide images that suggested the opposite about African Americans to mainstream white audiences. The Cosby show was born out of the need for counter images, and was successful in that it created a legacy of shows that followed which shifted representations of blacks more toward Cosby-ish types instead of overtly racist stereotypes, at least until the mid to late 90’s where buffoonish characters started to reappear. The Cosby show also had the negative effect however, of creating the trend of what Sut Jhally calls “enlightened racism.” The images that the Cosby show and its successors produced started to turn into those of the “exceptional” blacks, who were nice and familiar, and most importantly non-threatening to whites. The images also started to form sentiments, to be internalized by both whites and some African Americans as well, that blacks who didn’t make it only had themselves to blame, despite the race and class issues that existed during the times. Heavy focus on the Huxtables’ (Cosby’s family) as the ideal black family framed any Black family who didn’t fit into their high class way of life as failures. During a time where the Reagan conservative political atmosphere and philosophy of “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” was hitting its peak, the Cosby show justified individualistic sentiments, ignoring societal inequalities. What was created by the Cosby show was a Catch-22 where positive representations of African Americans were needed, however they came at the cost of blaming non Cosby-ish African Americans for their own struggle, and ignoring the need for an overhaul of widespread institutional racism.

Black-Ish follows a trend started by the Cosby show of representing African Americans, and more specifically African American families, as intelligent, successful, and loving, as opposed to poor, or violent, or buffoons, in order to counter these images that saturated the media. When the Cosby show aired, the black families seen on TV were either in the Ghetto and needed white aid to get out, or had made it out of poverty but the fact they now co-mingled with rich or middle class white people was a punchline. Many images of African Americans still portrayed them as comedic buffoons on TV, re-presenting old images of minstrels or “Coons.” Cosby understood how harmful these images were and saw a necessity to provide images that suggested the opposite about African Americans to mainstream white audiences. The Cosby show was born out of the need for counter images, and was successful in that it created a legacy of shows that followed which shifted representations of blacks more toward Cosby-ish types instead of overtly racist stereotypes, at least until the mid to late 90’s where buffoonish characters started to reappear. The Cosby show also had the negative effect however, of creating the trend of what Sut Jhally calls “enlightened racism.” The images that the Cosby show and its successors produced started to turn into those of the “exceptional” blacks, who were nice and familiar, and most importantly non-threatening to whites. The images also started to form sentiments, to be internalized by both whites and some African Americans as well, that blacks who didn’t make it only had themselves to blame, despite the race and class issues that existed during the times. Heavy focus on the Huxtables’ (Cosby’s family) as the ideal black family framed any Black family who didn’t fit into their high class way of life as failures. During a time where the Reagan conservative political atmosphere and philosophy of “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” was hitting its peak, the Cosby show justified individualistic sentiments, ignoring societal inequalities. What was created by the Cosby show was a Catch-22 where positive representations of African Americans were needed, however they came at the cost of blaming non Cosby-ish African Americans for their own struggle, and ignoring the need for an overhaul of widespread institutional racism.